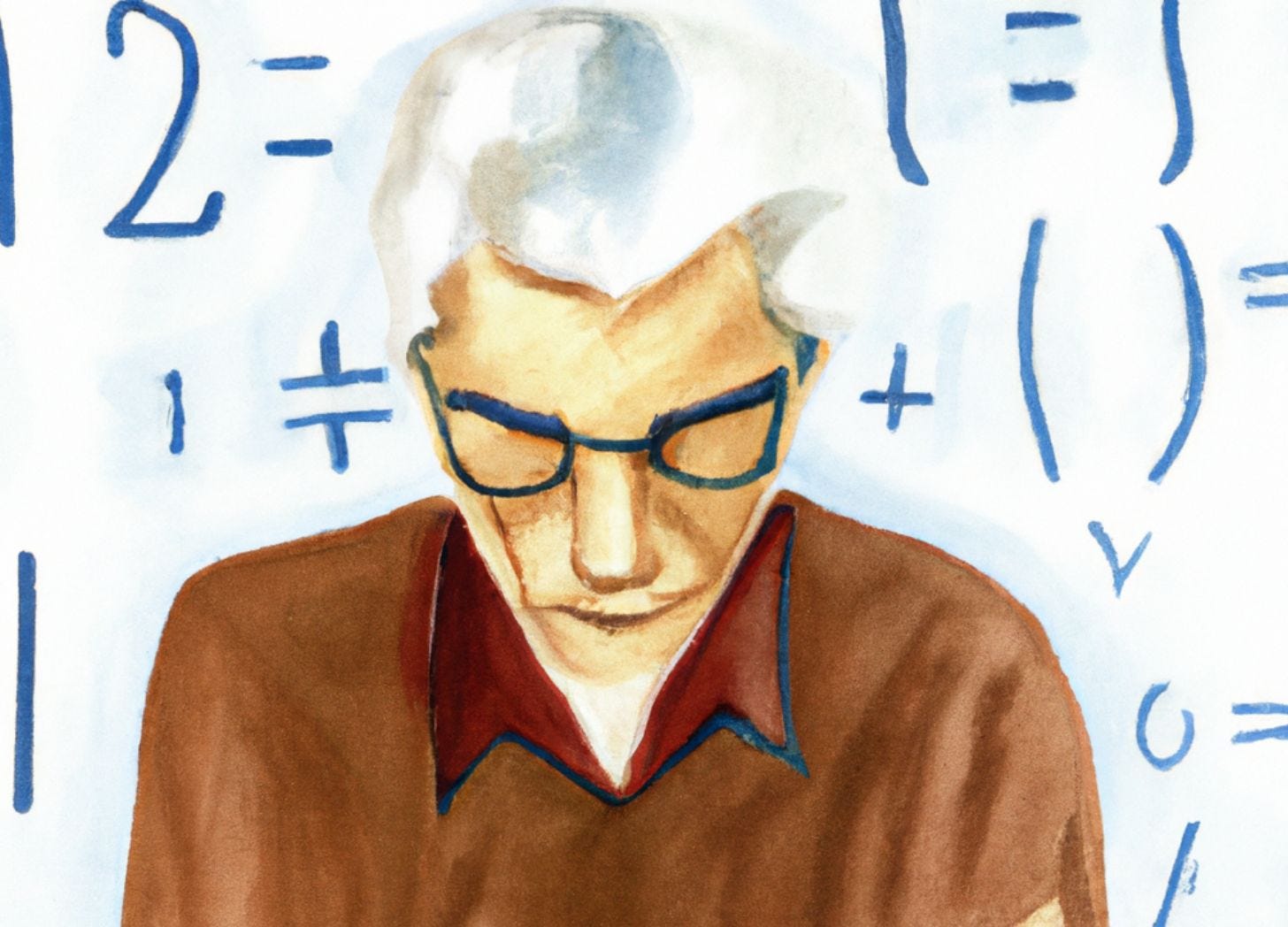

NEVER TOO LATE ... to study math

How the writer Alec Wilkinson set out to learn algebra, geometry, and calculus at age 65

Hi everybody -

Welcome back to Onward, a newsletter about life-long learning and personal reinvention. My end-of-the-year break was filled with outdoor activities, reading, and hanging out on the couch, so I feel pretty rested and ready for the new year. I hope you all had a good start to 2023!

Whether you plan to kick off a new personal project, continue with an ongoing undertaking or explore new possibilities out there for you, I am confident you will find inspiration and insight in this post and future ones.

New year, new format. Today I am introducing a column I am calling NEVER TOO LATE. It will host stories of people who went on unusual learning quests or embarked on new pursuits later in life. To make the content easily accessible and provide as much value for you as possible, I opted for a relatively formalized structure, as you will see below.

This first edition of NEVER TOO LATE features Alec Wilkinson, who decided at age 65 to study high school math. Alec’s story is unusual because he decided to try to learn something that he had previously failed to learn. Whereas most people with learning ambitions tend to revisit places of former successes or check out unfamiliar places they’ve always wanted to visit, Alec returned to a place of failure. How he went about it and what he found there is the topic of his new book, A Divine Language. Learning Algebra, Geometry, and Calculus at the Edge of Old Age.

WHO: Alec Wilkinson is a journalist, author of 11 books, and long-time contributor to The New Yorker. Before becoming a writer, he was a policeman and a Rock & Roll musician. He lives in New York City with his wife and son.

WHAT: At age 65, Alec decided to try to learn a subject that had left him feeling lost and stupid as a teenager, math. So he went on a two-year journey to study algebra, geometry, and calculus. “As a boy, I had been kicked off the math train at the algebra station,” he writes in The New Yorker, “so I decided to start there and then learn geometry and calculus—three of the disciplines that the eighteenth century called pure mathematics.”

He confesses that he passed algebra and geometry in high school by cheating, “which is not a good life lesson for an adolescent,” as he notes, but he had never taken calculus. “I didn’t even know what it was. It had always seemed less a subject than a destination, a private place where the bright girls and boys shared secrets.”

WHY: Why would an accomplished person in his seventh decade revisit something he has proved to be bad at 50 years earlier? Alec describes himself as a self-improver by nature, somebody who has read Proust and both the Old and New Testaments, studied French, meditated, and learned to draw. So he wondered why math had been so hard for him in high school.

Had I just fallen behind and never caught up? Was I not smart enough? Was I somehow unfitted to learn a logical, complex, and systematized discipline? Or was the capacity to learn math like any other attribute, talent for music, say? Instead of tone deaf, was I math deaf? And if I wasn’t and could correct this deficiency, what might I be capable of that I hadn’t been capable of before? I pictured mathematics as a landscape and myself as if contemplating a journey from which I might return like Marco Polo, having seen strange sights and with undreamt-of memories.

HOW: Alec didn’t want to take a class.; he had already failed math in this learning format. He didn’t want to be subject to the anxiety of keeping up with a class or slowing one down “because I had my hand in the air all the time.” In particular, he didn’t want a class for older people because “I didn’t want to be talked down to and more cheerfully than in usual life, the way nurses and flight attendants talk to you.”

So he recruited his niece, Amie Wilkinson, an accomplished math professor at the University of Chicago as a teacher. They talked on the phone and met in person, and in between, Alec sat at home over books and exercises. For two years, he spent his days “studying things that children study. I was returning to childhood not to recover something but to try to do things differently from the way I had done them, to try to do better and see where that led.”

Progression: To prepare for their first meeting, Amie suggested that he read Algebra for Dummies. He soon realized “that it didn’t matter who it was for, it was still algebra.” He was surprised to find math difficult because he assumed that in growing older, he had also grown smarter. As a boy, he didn’t know how to learn anything, he reasoned. Now, he was an accomplished grown-up who had mastered all sorts of things. “High school math, I expected to be totally within my capabilities. I expected to find myself thinking, How could I have found this so challenging [back then]?”

This is not what happened. He planned to allow six weeks to learn algebra. He figured that studying six hours a day, six or seven days a week, would give him about as much time as a student spends in a classroom in a year. But as the weeks passed and he noted all the pages left in the book, he began to question his optimistic expectations. Self-doubt crept in. “How can I have difficulty understanding what twelve-year-olds can?” he wondered.

When he felt he had read enough, he went to Chicago to see his niece. He describes how he sat beside her on a couch in her living room, holding his pencil and notebook ready. “My manner was like that of the novice on his first day in the monastery, poised to have the head monk reveal how to find God.” But instead, Amie said, “I’m not sure where to start.”

Alec came to understand that recruiting Amie might not have been the best decision. Some people in academia argue, he explains, that a subject is less efficiently learned from an expert than from a person who is still studying it or a recent graduate. “The adept’s long acquaintance makes it difficult for him or her to see the subject in its simpler terms or to appreciate what it is like to approach the subject as a greenhorn.” As he sat uneasily beside Amie, it was borne in on him that he was asking a mathematician with an international reputation to teach him math that she had learned nearly half a century earlier as a precocious child and hadn’t used since. After some weeks of working together in a stop-and-go fashion, he realized that he would have to learn much of what he planned to learn on his own.

The two years that followed were hard. He fought, he slogged, he revolted, he tortured himself, he dispaired. About twelve months in, he realized how much he had become separated from ordinary life.

My wife would leave for work, dressed differently each day, and I wore the same clothes all week. There was something solemn and monk-like about my confinement. For hours I turned the pages of books, and everything took place in my head. I might as well have been working by candlelight. It wore on my spirits to be removed from the rest of the world. Math became all that I did and thought about. I had an abstruse hobby, not a hobby, an obsession. Everyone was interested when it came up, but no one wanted to hear about it once they saw that I’d gone a little crackers with it.

OUTCOME: In the end, Alec had to come to terms with the fact that on his second encounter with math, he kind of flunked again. “[At the end of the two years,] I wasn’t really able to do mathematics,” he said in an interview on KQED. “As a student in school, I might have got a C plus or so. This story is not about some grand reconciliation, my triumph over mathematics.”

But even though mathematics didn’t seem to want to have much to do with him, as he writes, he doesn’t nurture a grievance against it. On the contrary, he found rewards and pleasures he didn’t expect:

I can still celebrate it as an idea carried down through history like a sacred knowledge by so many different minds, durable and adaptable and only partly explored and some of it, perhaps even much of it, presently out of reach entirely. It wasn’t my intention to become good at it, I wanted to submit myself to it and allow myself to respond to what it acquainted me with. Surely I wish I had done better at it, but it taught me not to be complacent in my thinking. An experience that only flattered my vanity would have taught me nothing at all.

He is pleased, he says, what learning of a pure type has done for him, pure meaning learning something he has no direct use for, like getting into college or preparing for a career change. In this passage, he describes some of the positive effects:

Despite my resistance and my incapacity, mathematics broadened me. By the close company of a discipline that insisted that I think and reason, I was enlarged. Like the philosopher at the dinner table, I understand the value of inquiry now and am more inclined to listen and less inclined to resist or pronounce. I assume that a problem has dimensions that I haven’t yet grasped or am even unaware of and that only a receptive examination can advance my understanding, meanwhile knowing—what I didn’t before—that all thought, all knowledge, all opinions and beliefs are everlastingly subject to revision.

This new understanding affects how he moves through the world, as he explains in the New Yorker: “It locates one in the present, and it lessens the abrasion. It encourages tolerance and engagement and nurtures the capacity to see the world as complex and not merely in terms of one’s advantage. It enables me to be more attentive to another argument, instead of rejecting it before I understand it.”

His experience even led him to notions of divinity, he writes:

Studying mathematics made me aware of a natural structure, elusively apparent and perhaps ultimately impenetrable. An implicit orderliness. An unfolding, moment by moment, on an apparently spectacular scale of something that no force can interrupt, something that is perhaps force itself. A trembling quality to life, both fearsome and fragile, a pattern that even to a novice like me is as clear as the grain in a piece of wood.

He is grateful to have learned all this, he points out, and wishes he knew who to express this gratitude to. What a great ending to an inspiring book!

Logo & Banner Design by Judy Higgins

Such an intruiging read. Though math is a subject I will never touch again, life is about exploring wherever our heart carries us. I will keep that in mind for my next excuse ... too old for this? Never!

I thorougly enjoyed meeting Alec and diving into his insights.

Thank you for this beautiful article, Annette 🍀

Glad you find Alec‘s story intriguing! I totally agree: Life is about exploring what one is passionate about, whether that is math or gardening or helping people or something else. And being passionate doesn‘t stop at age 25 or 35!