Not a subscriber yet? You are missing out! Sign up for the free subscription and you’ll receive emails every other week right in your email inbox. IT’S FREE! As a paying subscriber, you get additional newsletters with exclusive content and access to the full archive ($6 per month, $60 per year). Check it out! You can unsubscribe anytime.☀️

I have probably never been more immersed in a novel than when I read Doctor Zhivago at the age of 14. Lying on a sun chair during a family beach vacation in Spain, I binge-read about the drama of love and life in the Russian revolution and its aftermath. What I remember most vividly are Pasternak’s masterful descriptions of the harsh Russian winter, maybe because there were utterly contrary to my surroundings. Here is an example of a particularly frosty scene:

It was bitter cold. The streets were covered with a thick, black, glassy layer of ice, like the bottom of beer bottles. It hurt her to breathe. The air was dense with gray sleet and it tickled and pricked her face like the gray frozen bristles of her fur cape. Her heart thumping, she walked through the deserted streets past the steaming doors of cheap teashops and restaurants. Faces as red as sausages and horses’ and dogs’ heads with beards of icicles emerged from the mist. A thick crust of ice and snow covered the windows, and the colored reflections of lighted Christmas trees and the shadows of merrymakers moved across their chalk-white opaque surfaces as on magic lantern screens; it was as though shows were being given for the benefit of pedestrians.

Picture 14-year-old me: While everybody else on the beach around me was hiding under parasols or hanging out in the water, I persevered in the sun, glued to the paperback in my lap, at times even wrapping myself in a beach towel as I meant to feel the Russian cold. “Annette, it is over 100 degrees. You will get a heat stroke,” I still hear my mother scolding. “Go for a swim or at least get something to drink.”

But I couldn’t put aside the novel that described a world so dramatic, so complex, and so different from my own life as a high school kid from Cologne, Germany.

Getting immersed in a great novel is one example of what some psychologists and philosophers call a psychologically rich experience. Professor Shigehiro Oishi from the University of Virginia and colleagues developed this concept as a complement to two other well-known conceptions of the good life described by scholars: hedonic well-being (a happy life) characterized by comfort, joy, and stability; and eudaimonic well-being (a meaningful life) which centers on purpose, coherence, and societal significance.

As I explained in last week’s post, psychological richness stems from novel, unexpected, and complex experiences that change people’s view of the world and their place within it. While pursuing these activities, people feel engaged and awake and experience numerous deep emotions, from joy and excitement to anger and fear. Although not always positive, such experiences can form an integral part of what it means to lead a fulfilling life.

Today, I want to dig deeper into what activities and circumstances are conducive to building psychological wealth. Here are four essential insights researchers have gained.

One person’s most exciting experiences can be somebody else's greatest bore

What kind of situations and circumstances contribute to psychological wealth is a very individual thing. “Two people can have the same number of unusual experiences,” Oishi explains in an interview. “For one person, these experiences will add up to bring about new insights and perspectives. For someone else, they will remain interesting, yet disparate events that don’t contribute to growth.” Reading Russian novels might be eye-opening for me while doing little for you.

Why is that so? It has to do with personality, value systems, and mindset, as Oishi explains using the arts as an example: “If someone wants to live an aesthetic life, then engaging with thought-provoking art can be transformative for them, compared to someone who isn’t interested in these values. It also matters how reflective the person is. Self-reflection might be what binds experiences together to make them count toward a well-lived life. When we deeply reflect on our experiences, the connections and insights that we gather can accumulate to make for a richer whole.”

Psychological wealth is not the same as novelty-chasing or sensation seeking

A psychologically rich life is all about being open-minded and exploring the world. That doesn’t mean, says Oishi, “you have to chase after new and exciting experiences all the time. Rather, it’s an invitation to remain curious about life in its fullness, and not limit yourself to the comforts of what you already know. A person can go bungee-jumping for the sake of sensation seeking, and it might not change anything about the way they see life.”

Central to the notion of psychological richness is a change of perspective. When somebody is able to digest the novelty, complexity, and depth of an experience in new, insightful ways, Oishi explains, this is when a change of perspective is likely to occur, which in turn can lead to psychological growth.

Psychological wealth can be acquired by doing small things…

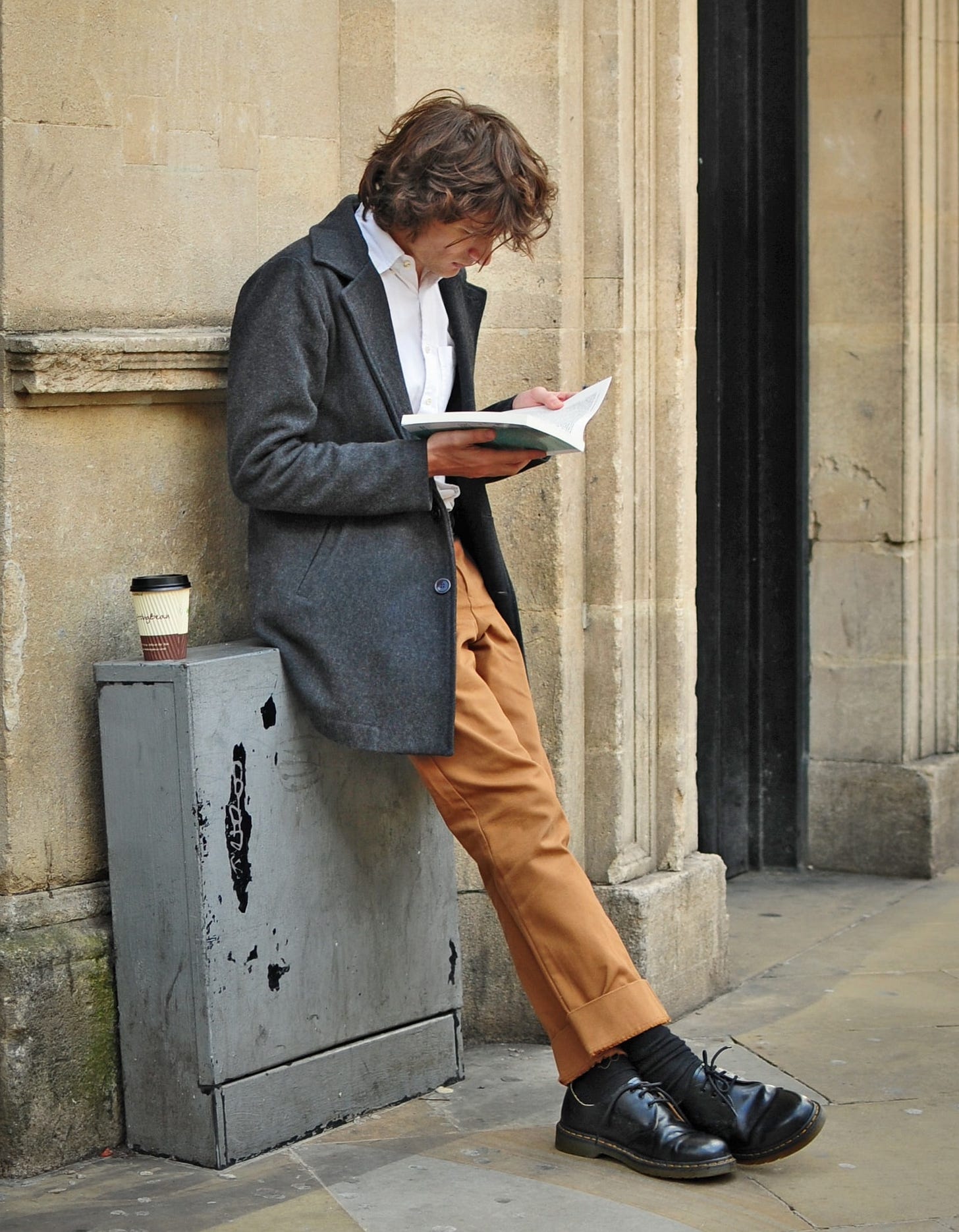

Engaging and perspective-changing experiences don’t have to be first-hand. We can engage with ourselves and the world indirectly through fictional characters, Oishi and his colleague Lorraine Besser write, feeling their emotional reactions to living very different lives than ours.

Take this fascinating study from Germany. The participants were assigned to read Der Vorleser (Engl. The Reader), a novel about a man struggling to make sense of his adolescent love affair in post-WW2 Germany with a much older woman (who was a Nazi concentration camp guard as the man later discovers and we as readers with him). The participants of the study didn’t feel happier after reading the book - which is probably not surprising given its theme. But they felt greater “delight” in reading over the course of the novel. How can this be explained? Such emotional shifts may be typical of complex, perspective-changing experiences that, while not always comfortable, are psychologically rich for those immersed in them, explain psychologists Westgate and Oishi.

Some books, pieces of art, or movies are more complex and evoke more change in perspective than others. Take this study in which researchers employed so-called figure-ground drawings. These images can be interpreted in two ways depending on whether you focus on the foreground shape or the background element. For example, one image the researchers used could be interpreted as a crescent moon but also as an upward-tilted face, depending on what part of the picture the participants focused on. In a series of experiments, such figure-ground drawings evoked greater psychological richness than the same drawings modified to remove the element that made the dual perspectives possible. “Some art makes the familiar unfamiliar, and the unfamiliar familiar; such shifts in perspective may be key to enriching our daily experiences,” the researchers conclude.

…and through pivotal or challenging life events

“Big” life events seem especially conducive to a psychologically rich life. Like immersing yourself in a different culture. Take an experience like studying abroad: Study abroad programs place students in unfamiliar environments for an extended period of time, forcing them to live differently than they did at home. In one study, Oishi and his colleagues recruited college students studying abroad, as well as students from the same university interested in studying abroad but who had stayed on campus. The scientists followed both groups for 12 weeks asking them to complete weekly surveys. Initially, there were no group differences in psychological richness, life satisfaction, or meaning in life. By the end of the semester, however, the study-abroad students reported significantly higher psychological richness than those who remained on campus.

These programs are often so transformative because they introduce students to new ways of thinking about life, Oishi says. In turn, they might become encouraged to engage with the novelty and complexity of the experience in ways that affect their understanding of the world which then leads to growth.

Oishi and his colleague Westgate also reflect on psychological richness as a coping mechanism in difficult life situations, like divorce, loss, and other tragedies. “Difficult moments are inevitable,” they write. “But by valuing them (and the perspective changes they bring), people may find value in experiences and lives that are not otherwise happy or meaningful.” This, however, might not happen automatically: “Psychological richness requires valuing not only the bright moments of life, but also the darker moments. For such experiences to contribute to psychological richness requires the ability to remember, actively reflect, and integrate those experiences. Thus, self-reflection and memory may be prerequisites for transforming experiential richness into psychological richness.”

One appealing aspect of the psychologically rich life, as Oishi and his colleagues point out, is that it is an accessible approach that people can pursue in many different ways. Some people structure their whole life around it, but interesting experiences are also available to people who find themselves stuck in an otherwise boring life. As we have seen, even small things like reading a novel or exploring an unfamiliar neighborhood can engage you and make you feel alive.

“A happy life is a great life. A meaningful life is a great life. But at times, when happiness and meaning are hard to come by, or if you are not predisposed to them, you can still experience well-being and have a good, admirable life by leading a psychologically rich life,” Oishi explains.

This feels like a very resourceful insight to me. More and more, I look at life through the lens of psychological richness. Not only do I seek out experiences that are perspective-changing, big and small. But I try to appreciate situations that feel challenging, awkward, or overwhelming - sometimes grudgingly, I admit - because I know they can add psychological richness to my life.

Logo & Banner Design by Judy Higgins